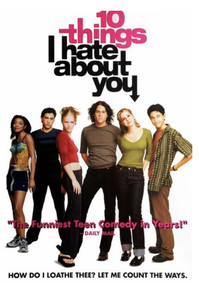

Yesterday was Craig’s birthday, and our independent movie theater was showing the 1999 film 10 Things I Hate About You. Despite being a GenXer like me, Craig has a penchant for 90s pop culture. Thus, it made for a good birthday date. Craig describes 10 Things as “one of the better films of its ilk.” I had never seen it** other than a scene I happened to walk in on while Craig was watching the film on TV a couple of years ago. I couldn’t tell you which scene it was, but I was unimpressed enough that I returned to whatever I had been doing. Hence last night, when the credits rolled and the audience broke into applause,*** Craig leaned over and said, “Thanks for sitting through that with me.” “It wasn’t bad,” I replied as we gathered our things. I could easily see its appeal. It’s Gen Y’s The Breakfast Club, capturing a time and place through music and fashion and the classic tropes of adolescent love and angst and belonging with comedy. It made the case that Shakespeare isn’t dead. Yet overall, I still wasn’t impressed. I aired my grievances as we walked downtown to the car. Aside from jokes that landed poorly with me (namely, “Kat didn’t take her Midol this morning” and “My insurance doesn’t cover PMS”), I argued that the movie missed several opportunities for something deeper. “Comedy doesn’t have to be all zingers and slapstick,” I said. “A good comedy—especially a good romantic comedy—also reveals vulnerability.” For example: In When Harry Met Sally… when cool, collected, organized Sally is finally melting down about her ex, grabbing and tossing tissues over her shoulder while Harry observes, she calms down for a moment and confesses: “All this time I’ve been saying he didn’t want to get married. But the truth is, he didn’t want to marry me.” It’s a moment of vulnerability. Of poignancy. Of pathos. It’s the moment we finally understand why Sally is Sally. We understand everything. And the comedy returns on the next beat even amidst her vulnerability. 10 Things I Hate About You missed such an opportunity, for example, when Kat yells at her father, “Just because you can’t control your own life doesn’t mean you get to control mine.” The moment could have been softened with a revelation from her father: “Did it ever occur to you that I’m terrified to lose you the way I lost your mother?” Then, instead of a bumbling, irrationally overprotective father and a daughter with righteous indignation, we’d see a family that's suffered an explicable loss and have been projecting their grief onto one another. We’d understand why they are the way they are. I offered another example of a missed opportunity via showing vs. telling. In Julie and Julia,**** as Paul and Julia Child stroll the Paris streets, a woman pushing a baby carriage passes them in the opposite direction. Julia’s expression at the point of passage reveals all: She is childless. And even though we don’t know why, we now know that it hurts her deeply. It is a brilliant, fleeting moment of darkness in a character who is full of light. Contrast this with 10 Things, when Patrick doesn’t dispel the rumors of his formidable past until he and Kat are on a loud, crowded dance floor at the prom, and the truth is far less nefarious. The revelation almost goes unnoticed, as if it’s insignificant. What if, when Patrick drove a drunk Kat home from a party, she saw a photograph on his dashboard and asked about it? What if he answered her question simply without any exposition: “That’s my grandfather”? We would then know his past isn’t what we think it is—that he isn’t what, or who, we think he is. We would see so much without needing to know the details. And don’t get me started on what a missed opportunity Allison Janney’s character was. Allegedly, when director and screenwriter George Seaton visited Academy Award-winning actor Edmund Gwenn as he lay in bed ill, Seaton said to Gwenn “This must be terribly difficult for you.” Gwenn was said to have replied, “Dying is easy. Comedy is hard.” The misconception of a good romantic comedy is that it is light. It’s easy. It’s all about the laughs and the absurdities of love and romance. Yet the true mark of a good rom-com is that, underneath every I’ll-have-what-she’s-having, laugh-out-loud line or scene, there is something hard and real and sobering: the gripping fear that we are not loved or lovable. How a character comes to terms with that is what draws us to the story. Moreover, it’s why we need to write the story in the first place. * I know. I’m posting this in the afternoon. But I wrote it this morning. ** This might seem absurd to some until they understand just how entrenched I’ve been in the 80s for the last 40 years. That said, had I been 14 years old in 1999, I would have had a massive crush on Heath Ledger. *** I now can’t help but hear the Progressive Life Coach say, “No one who made the movie is here” when moviegoers applaud. **** I didn’t set out to use Nora Ephron film examples, but hat-tip to Nora—and the films themselves—for having been so good at it. Comments are closed.

|

Archives

June 2024

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed